This Blog is an older article from me, i believe from mid’2014. But i will probably re-edit it in the near future.

Katori Shinto-ryu is one of the oldest extant Martial Arts of this world. Her origin is tightly linked with the Katori Dai-Jingu[Great Shrine], one of the oldest and most important Shinto Shrines in Japan, only exceeded maybe by the Ise and Kashima Dai-Jingu.

This three Great Shrines, or more accurate the kami associated with the shrines: Amaterasu no Mikoto(Ise), Takemikazuchi no Mikoto(Kashima) and Futsunushi no Mikoto(Katori), play an important part in origin mythology of Japan written down in the Nihonshoki and Kojiki.

Amaterasu is the japanese Goddess of the Sun and claimed Ancentress of the Japanese imperial House. She gave both Gods of War, Futsunushi and Takemikazushi the order to descend on Izumo to negotiate with Okuninushi no Mikoto about the surrender of the Land to Amaterasus Grandson, Ninigi no Mikoto.

After Okuninushi surrenderd, both Futsunushi and Takemikazuchi lingered on earth. Futsunushi marched to the East and fought Demons and other evil Kami who scourged the Land. This way he added new parts to the Kingdom and trough his martial skill lay foundation for a wealthy and secured country Japan.

Takemikazuchi assisted Jimmu Tenno, descendent of Ninigi and founder of the imperial House to subjugate further Land in the East. [It must be noted that the Myths differ and maybe both, Futsunushi and Takemikazuchi could be names for one and the same Kami. But i will probably write more about this in another Blog.]

It’s transmitted in Katori Shinto-ryu that the founder Iizasa Choizai Ienao settled in proximity of the Katori Shrine at the age of 60, after becoming a buddhist Nyudo[Lay priest]. There at the shrine he devoted himself to martial, ascetic and spirituel exercises every day and night. After 1000 days he had a visionary dream. There he meet Futsunushi as a young boy, sitting on a plum tree. Futsunushi gave Choizai a scroll, the Mokuroku Heiho no Shinsho, and transmitted to him the heavenly secret Techniques of martial arts and Strategy. Through this heavenly wisdom he founded Tenshin Shoden Katori Shinto-ryu Heiho. The Tenshin Shoden part translates in „Heavens true and correct transmisson“. Meaning the transmission from Futsunushi to Choizai.

Most students of Katori Shinto-ryu know this of course. But many are not aware about the role of the buddhist Goddess Marishiten in the whole story.

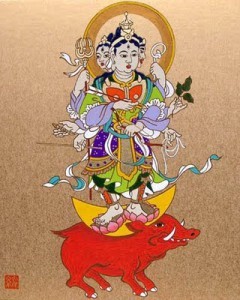

Marishiten is a goddess of war and patroness of warriors. The deity is often shown as a woman with three heads or faces, eight arms and different weapons in the hands. She also a Deity of the Dawn and Dusk with power over Sun and Moon. She is driving with her heavenly carriage pulled by seven Boars on the heavens.

But sometimes she’s also portraited as Man, which shows she is incorpurating female and male aspects. She is granting the warriors who pray to her with incarnations and mudra help trough blending of their foes with bright light. This way her proteges become invisible to their enemies.

Next to Marishiten exist also other tantric warrior Deitys which get referred in different Ryuha[Styles/Traditions] like Bishamonten and Fudo-myoo to name a few.

Which special role Marishiten plays in Katori Shinto-ryu can be found in the Katori shinryo shinto-ryu kongensho [godly origins of the holy Swordtradition of the Katori Shrine] scroll:

„Through a divine vision, Marishiten taught Futsunushi no Mikoto that there are divine sword scenarios known as Itsutsu, Nanatsu, and Kasumi, and divine spear scenarios known as Hakka. Marishiten also brought one volume on strategy and displayed a sword called Ame no Totsukanomi Tsurugi“

p.214, D.Hall 2013, The Buddhist Goddess Marishiten

Which means the knowledge transmitted by Futsunushi has his origin by Marishiten The scroll further explains which meanings this Scenarios of Katori Shinto-ryu are holding:

„The spear techniques(Hakka) and sword techniques (Mitsu no tachi, Nanatsu no Tachi, and Itsutsu no Tachi) are all elements of the self-defense ritual matrix. The first element is the Purification of Body, Speech, and Mind […] . Collectively, the four elements are a single one of Body Armoring (Hikô goshin 被甲護身). “

p. 215, D.Hall 2013

Which shows that the techniques of esoteric tantric buddism weren’t only simply a part of the curriculum but the whole curriculum of the School was heavely linked to this rituals in the beginning next to the pure martial aspects of the Tradition.

Marishiten gets called trough use of Kujiho[Fingersigns] and Jujiho[drawing in the hands with ones finger] and an incarnation from japanized sankrit.

The point of this different rituals, which seem for most western people probaly nothing more like esoteric superstition, is to reach trough meditation a state of mind where one is fearless and literally believes to be invincible(because of the protection of Marishiten and Futsunushi) and to link it to the Finger and Handsigns of the Kuji- and Juji-ho. Thus this signs become anchors to instantly activate the wanted state of mind which should lead to a better performance in battle.

„Ôtake Ritsuke believes this to be the case, and feels that the performance of the Goshinpô and the Kuji no Daiji were much more efficient for battlefield preparation than the practice of zazen.“

p.216, D.Hall 2013

These rituals weren’t done and transmitted because of reasons of pure faith. But because they showed an effect at manipulating the warriors state of mind. Which, of course got amplified by a strong enough faith in the deity.

So the next time before a training session i bow not only in awareness to Choizai and Futsunushi, but also Marishiten.

Resources:

- David A. Hall, The Buddhist Goddess Marishiten: A Study of the Evolution and Impact of Her Cult on the Japanese Warrior

- Risuke Otake, Katori Shinto-ryu : Warrior Tradition